Celebrating Dublin’s Built Heritage talks

12.08.2020

Posted by IGS

Image: Pembroke Estate map depicting Upper Baggot Street, reproduced courtesy of National Archives of Ireland.

CELEBRATING DUBLIN'S BUILT HERITAGE TALKS

To mark National Heritage Week 2020, Dublin City Council invited the Irish Georgian Society to partner on the curation of a series of twelve free on-line talks that celebrate aspects of Dublin’s built heritage.

The lectures are broad in their subject matter, addressing themes ranging from domestic life in the Victorian house, 20th century concrete architecture, Georgian speculative development, industrial heritage, Masonic philanthropic endeavours, Tractarian church architecture, and an exploration of an exhibition of Dublin's architectural fragments, to name a few.

These lectures will be available to watch free of charge for the duration of National Heritage Week (Saturday 15th to Sunday 23rd August) through the Events page on the Irish Georgian Society’s website https://www.igs.ie/events

- Ambition & Architecture: The RDS, Ballsbridge by Professor J. Owen Lewis, President, Royal Dublin Society (Learn More)

- St. Bartholomew's Church, Clyde Road, Dublin 4: a heritage exploration with Dr Alistair Rowan, founding editor of the Yale University Press Buildings of Ireland 'Pevsner Architectural Guides' (Learn More)

- Oh, Glorious Precast: Hot Concrete in Ballsbridge by Shane O'Toole, contributor to More Than Concrete Blocks: Dublin City's Twentieth-Century Buildings and Their Stories (Four Courts Press & DCC, 2016 & 2018) (Learn More)

- Establishing a Suburb: Early building development in the Pembroke Estate outside the Grand Canal by Dr Eve McAulay, Irish Architectural Archive(Learn More)

- The Masonic Female Orphan School Ballsbridge Dublin by Rebecca Hayes, Curator and Archivist at Freemasons’ Hall, Dublin(Learn More)

- Upstairs, Downstairs: Dublin’s Victorian houses by Dr Susan Galavan, author of Dublin’s Bourgeois Homes: building the Victorian suburbs 1850-1901 (Routledge, 2017) (Learn More)

- Tracing the Industrial Landscape of the Pembroke Township by Mary-Liz McCarthy, Assistant Architectural Conservation Officer, Dublin City Council (Learn More)

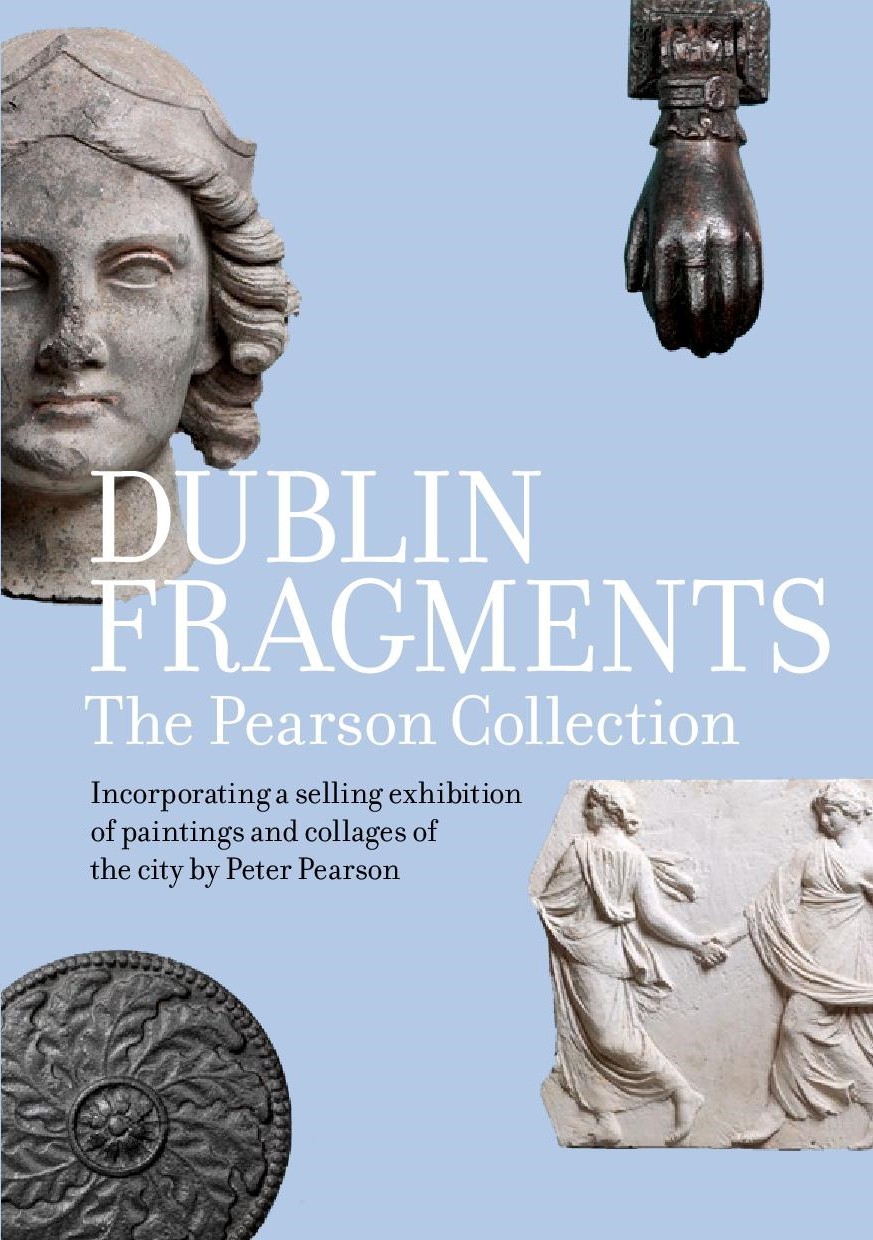

- Dublin Fragments: The Pearson Collection, tour of the Irish Georgian Society’s City Assembly House exhibition with curator, Peter Pearson in conversation with Charles Duggan, Dublin City Council Heritage Officer (Learn More)

- Our Lady of Refuge Church, Rathmines: patron and architect by Dr Brendan Grimes, Buildings of Ireland (Learn More)

- Sensitively Adapting Period Houses to Contemporary Life by David Averill, Director, Sheehan Barry Architects(Learn More)

- "..All the World's a Stage", how the everyday forms the character of our spaces by Niamh Kiernan, Architectural Conservation Officer, Dublin City Council (Learn More)

- Dublin's Townships by Séamas Ó Maitiú, author of Dublin's Suburban Towns, 1834-1930: Governing Clontarf, Drumcondra, Dalkey, Killiney, Kilmainham, Pembroke, Kingstown, Blackrock, Rathmines, and Rathgar (Four Courts Press, 2003) (Learn More)